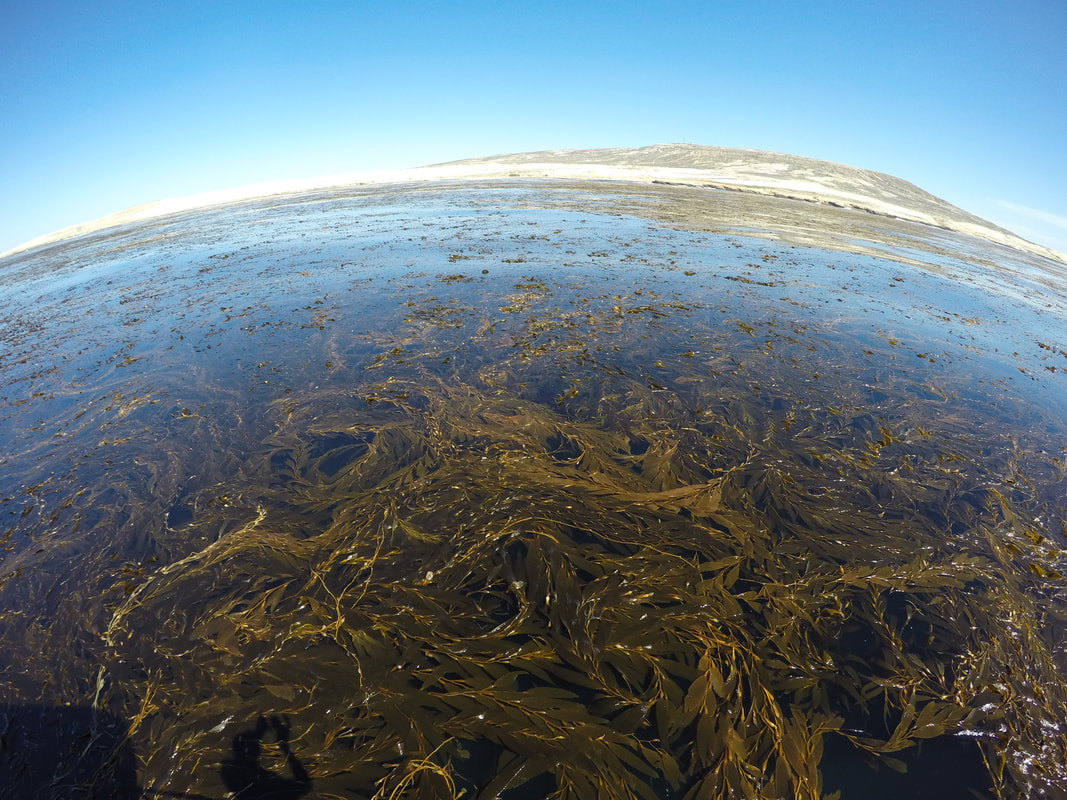

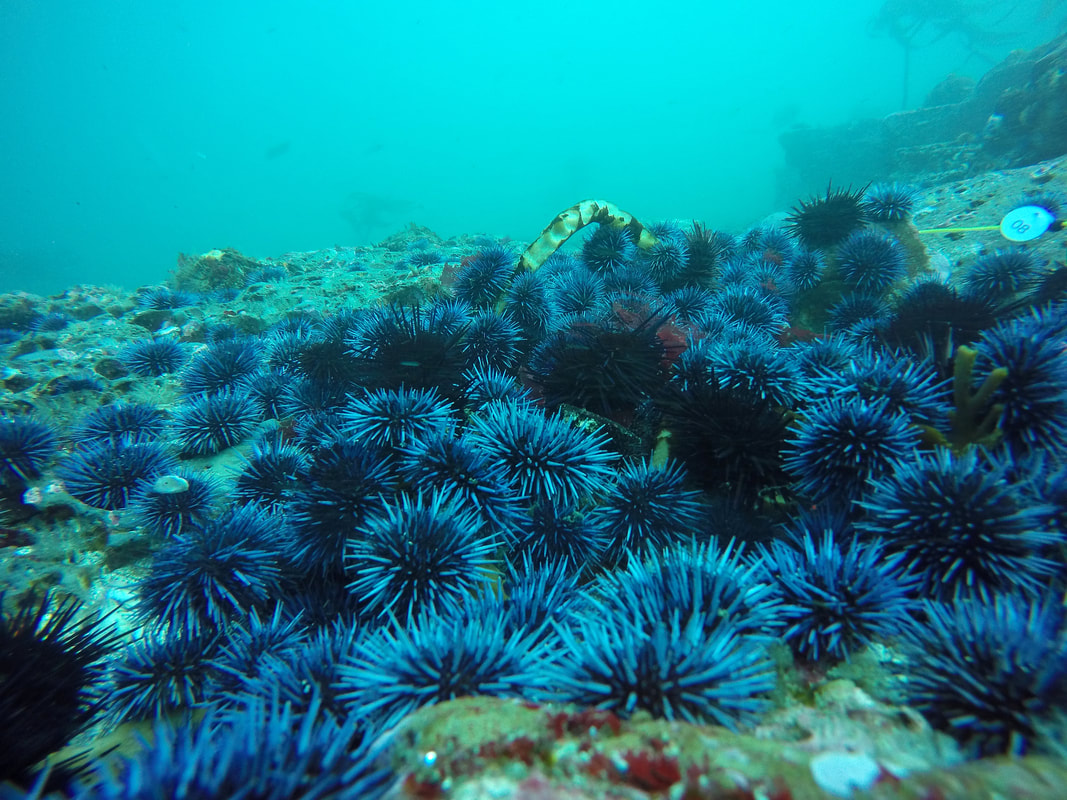

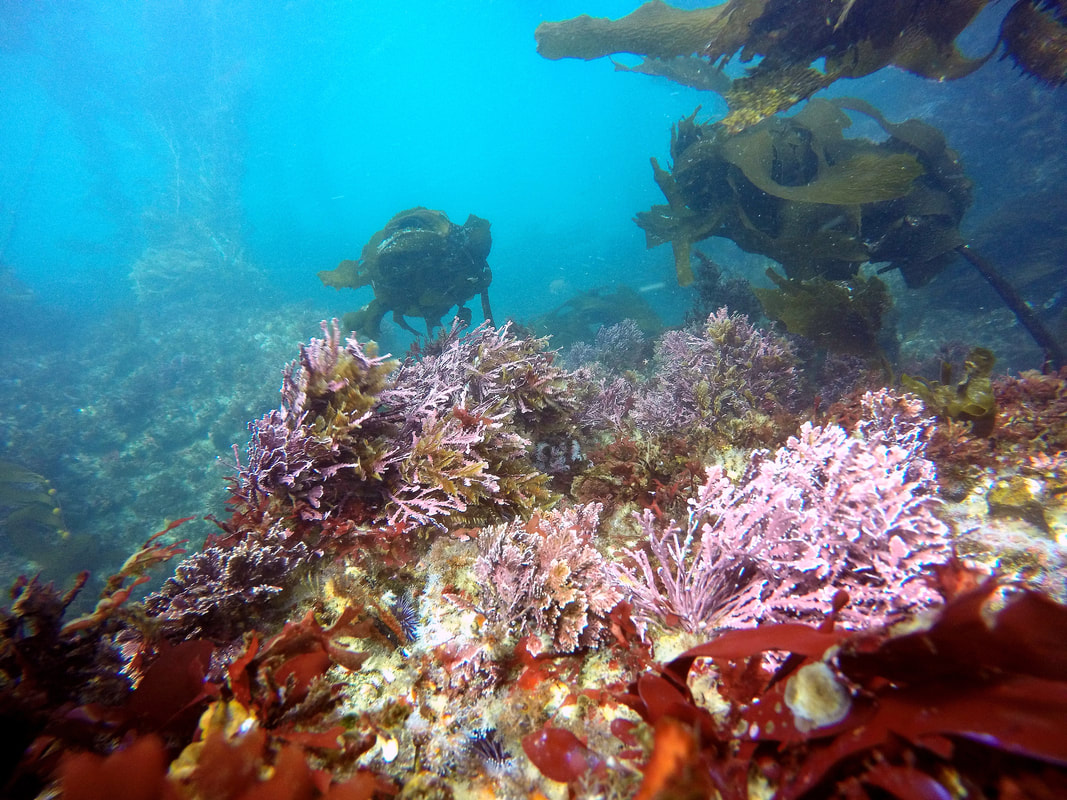

The need for long-term monitoring – what geographic isolation can tell us about kelp forests4/1/2018  West end SNI. Look at all that glorious kelp! Photo by Z. Randell West end SNI. Look at all that glorious kelp! Photo by Z. Randell April 1st, 2018 Los Angeles, CA Battered by wind and waves, San Nicolas Island knows the full force of the ocean’s fury. The most remote of the Channel Islands, San Nicolas sits approximately 100km off the coast of Southern California, and more then 50km to its closet neighbor, Santa Barbara Island. San Nicolas Island (SNI) is currently controlled by the US Navy, and while the island is technically uninhabited, there are about 200 military and civilian personnel on island. So, what does a remote military island have to do with kelp forest ecology? I’m glad you asked. Due to the relative remoteness of the Channel Islands, the island chain is home to some of the most pristine and prolific kelp forests in North America. Five of the eight islands are under the National Park Services’ protection, and the kelp forests have been studied every summer since 1982 . In fact, the data collected from the Kelp Forest Monitoring Program has been used in many major scientific publications. And while SNI might boast some of the most pristine kelp forests in Southern California, the Navy restricts access to SNI; the island is all but inaccessible to your average recreational divers. Enter the US Fish and Wildlife (USFWS) Service and the US Geological Survey (USGS). In 2014 the USGS established a kelp forest monitoring program for the US Navy, “building on sites established by the USFWS in 1980” (Kenner 2018). For the last three years, the USGS has been sampling four sites biannually, collecting information on the organisms that live there, the physical marine environment, and the underwater community as a whole. The long-term monitoring sites established at SNI help scientists understand what a kelp forest (that is largely unperturbed by humans) can look like, at least in southern California. While scientists have been studying kelp forests for at least a century (or more!), we don’t really have access to places that humans haven’t had a heavy hand in, especially in southern California where coastal development is just one of many anthropogenic (human-derived) disturbances affecting the nearshore environment. So, not only does SNI afford us a glimpse into what kelp forests in California could look like, there’s something even more unique about SNI. Between 1987 and 1990, 140 sea otters (Enydra lutris neries) were introduced to SNI (Hadfield 2005). Historically, sea otters were found from Kamchatka (Eastern Russia) all the way to Baja California’s southern kelp forests. We know that, at least in Alaska, otters play a major role in regulating kelp forest communities. However, the Russian fur trade pushed them to the brink of extinction by the middle of the 19th century. Since their listing as an endangered species in 1971, the California population of sea otters found near Point Sur in 1915 has spread north to Santa Cruz and south to Point Conception. While the state of kelp forests in Southern California is in flux, we understand that the century-long absence of sea otters has likely impacted the nearshore environment. The point here is that our understanding of kelp forests, as wide as it might be, is incomplete. We need healthy and vibrant kelp forests to protect our coastlines from storms, draw down atmospheric carbon dioxide, and provide habitat for commercially desirable species. So, how are otters assisting in balancing kelp forest ecosystems? The presence of sea otters at SNI has shown us what a healthy kelp forest can look like. Sites that were previously urchin-dominated (much like the urchin barrens in the Aleutian Archipelago) have returned to their gloriously kelp-dominated state as the otter population continues to grow. While there are pristine kelp forests left in this world, they are largely inaccessible, which is partly what makes surveying SNI so exciting. But the novelty of the SNI kelp forest monitoring doesn’t stop at the surface. This ambitious protocol facilitates collaboration between scientists with the USGS, the US Navy, researchers at UC Santa Cruz and even faculty at Oregon State University. We may never know what a truly “wild” kelp forest looks like, but long-term studies like this help fill in gaps in our knowledge regarding these vital ecosystems. As the world continues to change, studies like this will inform adaptive management, and may help lay the foundation for mitigating some of the impacts humans have imposed.

I have been lucky enough to be offered a volunteer spot on this April’s sampling trip with the USGS, so stay tuned for updates from the most remote Channel Island! Cheers, -Baron von Urchin P.S. For those of you who read, "Island of the Blue Dolphins", it's based on the incredible true story of Juana Maria, the last Nicoleño of San Nicolas Island!

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorPike Spector is currently a Research Operations Specialist with Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary Archives

August 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed