|

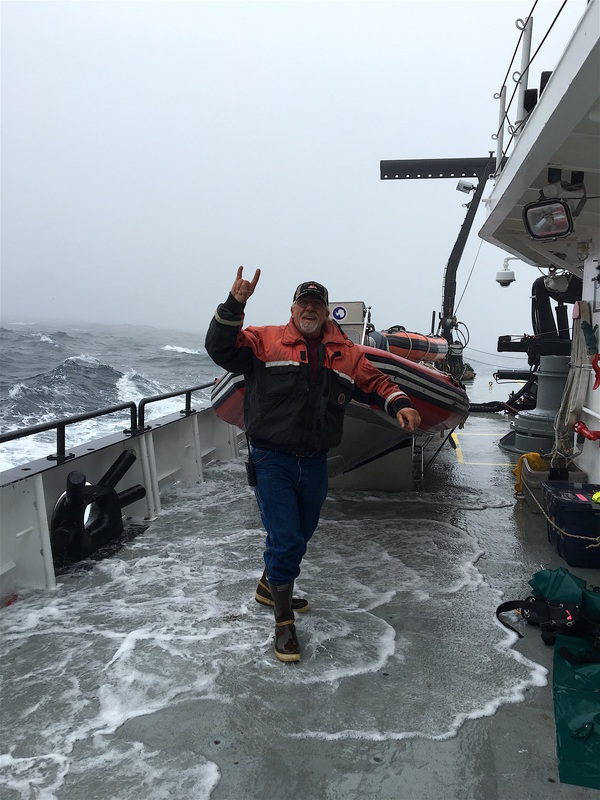

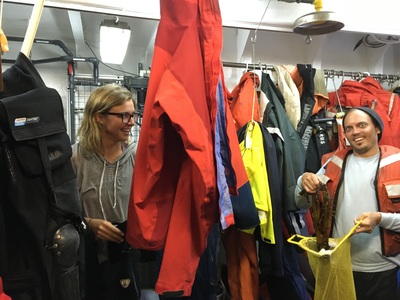

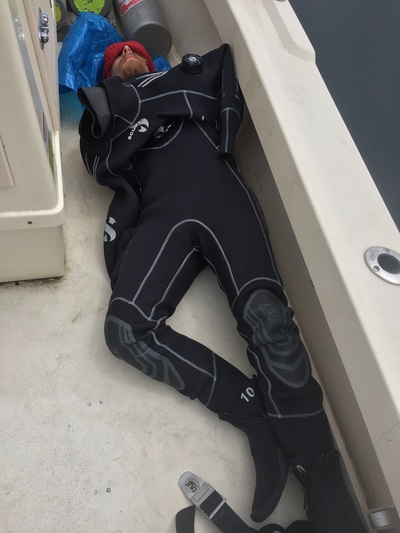

R/V Oceanus: Chuginadak 6/24 – 6/26 As we departed Atka under sunny skies and a slowly diminishing swell (which still left us battered and bruised from our chamber recovery mission) we set sail to the east, for the island of Chuginadak (Chuggin-ah-dak). Before we leave each each island, the Konar lab and the Oceanus’s crew set out trawling gear for short intervals. Part of this project involves looking at kelp subsidies to offshore ecosystems; that is, how much kelp material is being transported into deeper waters which can then be used as food for other organisms. After the trawl we began our transit. For the next 18+ hours we were pounded by over 10ft waves and 30knot winds, not the most pleasant sailing conditions. One of the engineers muttered something about us at least heading down seas, but either way it was a bumpy ride. Fortunately, there wasn’t really a whole lot to do, so everyone did their best to catch on some much needed sleep. We’ve all been trying to “rack-out” as close to midnight as possible, but on most nights that’s just not possible. The day-long steam passed uneventfully, aside from a particularly nasty wave that managed to break a tie-down line that was holding down some of our dive gear. Fortunately, Doug and I were able to re-secure everything before any of it was lost. After a long day in the storm everyone was more than relieved when we dropped anchor at Chuginadak, right under the slope of an immense volcano. Our anchorage was surrounded by mountains, but four of the volcanos really stood out once the fog cleared. As part of this project we were hoping to walk some of the islands’ beaches for otter carcasses (and some “Aleutian treasure”) but up to this point we hadn’t had any time to do so. On Chuginadak everybody in the Edwards’ lab was frothing to go ashore, and on our second and final day we were finally able to stretch our legs. Landing on any of the islands is no easy feat; one has to find a safe place to run a boat in as close to shore as possible, without flipping in the surf. In more tropical places a little bit of submersion is OK, but without proper immersion protection (like drysuits) things can turn ugly very quickly. Fortunately, six of us went ashore without any issues. Living on a boat for a week can make you a little claustrophobic; after a few perplexing minutes of standing next to one another on the sandy beach, we each dispersed for a little solitude. Chirping birds, a gentle breeze through the grass and the smell of Arctic wild flowers were a much welcomed change of pace from the hum of a diesel engine and the smell of algae (and other things) in the wet lab. But all too soon we had to head back to the Oceanus; at this point we still had to eat dinner, collect our chambers and sort our samples before heading to the next island. I’m pleased to say that our chambers were deployed and recovered without any issues. After Adak and Atka, I think our lab has this whole chamber thing on lock. Phycology Team 7. Working in the Aleutians has had its challenges, but I’ll never get tired of steaming to dive sites under snow covered mountain, volcanos and grassy, windswept shores. Coming up from a dive under a volcano, with another in the distance, is certainly a unique experience. Have you ever wondered what it’s like to dive in the Bering Sea? First you’ve got to learn how to dive in a drysuit, and master all of the associated bells and whistles, which is easier said than done. Swimming in a drysuit through a kelp forest is like trying to pull an inflated trash bag filled with lead weight through the water. To reduce drag, we do our best to be streamlined, like a fish. Being “trim” helps us swim through a relatively challenging and inhospitable environment as efficiently as possible. But we’re not here just to look good underwater, our job is to conduct experiments and take good data (a year’s worth of data in three weeks, remember?) SCUBA diving has become a much safer recreational activity, and scientific diving takes it to a whole new level. As a science diver you still work on your trim, but only after you’ve attached all of the tools you’ll need on a given dive. PVC poles fashioned into squares (aka a quadrat), meter tapes, and slates to write on are just a few of the typical things you’ll find clipped to a scientific diver. Now factor in the drysuit, which is kind of like diving in a vacuum-sealed rain jacket. Add on base layers, heavy undergarments, and about 30 more pounds of lead weight than you’d typically wear with a typical a wetsuit, and you’ll get an idea of what it’s like. 5mm gloves limit dexterity (but so do frozen fingers so it’s a give-and-a-take) and a 7mm hood helps seal in as much warmth as possible. We struggle into our undergarments and blast through inclement weather just to buy about an hour underwater. But believe me, it’s worth it. I wouldn’t trade this for anything. One of the most important things you can bring into the field out here is a thermos full of piping hot water. After a 30min dive we use the buddy-system (integral to diving in general) to pour hot water into each other’s gloves to try to bring back some sensation. Oh, you might be wondering about the vacuum part of this analogy. To fight off “suit squeeze” (because everything compressible compresses at depth) we pump in air from our tanks into our drysuits. A wetsuit works by trapping a layer of water between you and the neoprene, allowing your body heat to warm the water. A drysuit does the same thing, but with air inside the suit; the base layers help seal in that heat. Well, that’s it for this phycological update. We’re continuing our eastward journey, across the Samalga Pass, to Umnak Island and our next sampling stations. And, as always, don’t forget to tune in to the Edwards’ Lab blog! From left to right: one of Chuginadak's volcanoes through the native tussock grass; the dragon kelp Eularia fistulosa; Ben filleting a freshly caught halibut during much cherished down town; returning to the Oceanus after a dive

1 Comment

R/V Oceanus: Adak and Atka 6/19 – 6/23 |

AuthorPike Spector is currently a Research Operations Specialist with Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary Archives

August 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed