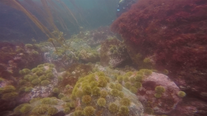

Once the fog cleared, Yunaska's fascinating rock faces were revealed to us Once the fog cleared, Yunaska's fascinating rock faces were revealed to us Yunaska and Unalaska Island 7/23-7/25/17 After a short steam from Atka, we dropped hook on the small, volcanic island of Yunaska. All of the Aleutians are volcanic in nature (see Bogoslof which erupted two days after our initial departure from Adak), but Yunaska is something else entirely. Once the dense, persistent fog, infamous in the Aleutians, finally lifted, we were awestruck by the landscape. Towering volcanoes gave way to exposed hillsides and rock faces dropping straight into the sea. A quick look at the charts confirmed our suspicions; we were in the middle of Crater Anchorage, the blast crater from a massive eruption in 1927. Most of the time, visibility at depth in the Aleutians is pretty good (around 10 meters or so)—that is, until we stir up clouds of silt from the bottom by putting our chambers down or collecting samples. However, on Yunaska “the vis” was incredible; easily over 20 meters. Watching from the surface, I had a clear view of our chambers when we puttered over them in the small boats. Even though I can’t get in the water for another month or so, I was thrilled to be on the water in Yunaska. While the dive teams were rounding off the data collection on our last island, I kept myself busy in the lab by entering and analyzing data and sorting samples as they came back. Some might say that this project is over-ambitious, but collectively we were able to make everything happen. It really is an incredible thing, attempting to collect a year’s worth of data in about a month. But the teams up here are mission-oriented; our days are long but spirits are always high. Our last day on Yunaska was one for the books. The fog came and went in rapid dark grey eddies, leaving stillness and sunshine in its wake. The colors of the island, above and below the surface, came alive. You could feel the energy on the Oceanus. Yunaska is our last island for this whole project, and we had to make it count. But all too soon it was time to begin our day-long steam to Unalaska and our departure from Dutch Harbor. The last day on the Oceanus was bittersweet; as we packed up our dive gear and broke down the labs we reminisced about our two summers in the Aleutians. These islands are incredible, but the people that make up the dives teams really made this experience exceptional.  The Edwards Lab (and Ben from the Konar Lab) pose in front of a map of the Aleutians at the Museum in Dutch Harbor The Edwards Lab (and Ben from the Konar Lab) pose in front of a map of the Aleutians at the Museum in Dutch Harbor On the morning of the 25th we arrived in Dutch Harbor, the most populated place in the Aleutians. As part of this project, our Labs were asked to collaborate on an exhibit in the Museum of the Aleutians in Dutch Harbor. We were invited to tour the exhibit, which pulls together our project along with geologic and anthropologic research across the Aleutians. The exhibit even featured a small video, put together by yours truly. After a long day in Dutch, we boarded our plane, bound for Anchorage. We said our bittersweet goodbyes at the airport, after more than a little celebrating in Dutch. This wraps up the second of our two research cruises in the Aleutian Archipelago. It has been an incredible journey, but it’s not over yet! While we’ve finished collecting our data, we still have a whole lot of analysis and writing ahead of us. Be sure to check back in as we delve into the data and the story really develops! This is Baron von Urchin checking out from the Great White North.

0 Comments

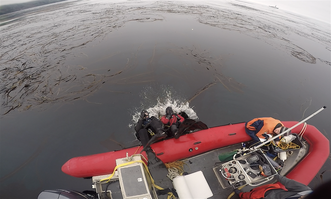

Blast off! The Wecoma (grey inflatable) and the Oceanus RIB take off to retrieve our chambers Blast off! The Wecoma (grey inflatable) and the Oceanus RIB take off to retrieve our chambers Atka Island 7/21/17 Last year, Atka was the third of the six islands we sampled. By the time we had gotten there we had “cut our teeth” on Tanaga and Adak. Even still, Atka had given us a solid run for our money. So this year, when we heard that we were going back to Atka, we all exchanged a glance. But, on the morning of the 20th when we awoke at the same anchorage as last year, we were greeted by the same towering waterfall, the same rolling hills and steep cliffs, the same imposing rocky coastline. We were back, and more than ready to jump in the water. Well, I should say, everyone else was more than ready. After my little incident on Kiska I won’t be diving for the rest of the trip. However, in the water or not, there’s always something to do in the lab, or with the data we’ve already gathered. You can take the diver out of the kelp forest, but in this case you can’t take the kelp forest out of the diver. Between helping sort samples, writing reports and analyzing the light and oxygen data I managed to keep busy. At the end of the day, we’re doing a year’s worth of field work in just about three weeks. We can all feel the strain this puts on us, but we’re unified in our collective goal; to “get the data!” Everyone on this trip has invested considerable energy and time to get here. We’ve all made sacrifices, in some for another, and nothing can slow us down at this point. So, instead of feeling sorry for myself, I picked up a pen and jumped into the fray. As I’ve mentioned before, sea urchins are a huge part of the story up here. Part of what we’re doing is gaining an understanding of the population dynamics of the urchins in the urchin barren grounds. On every island we easily collect over 1000 urchins from the barren grounds and measure them in the lab. We can correlate the length of the urchin’s test (the diameter of the urchin’s exoskeleton between the spines) to its weight. Urchins are little grazing machines who efficiently turn algae into caloric energy that they use for reproduction. A fat urchin is a healthy urchin, and a healthy urchin tends to be very reproductive. How does this impact the longevity and persistence of the barren grounds? What role does disease play in population regulation? These are just some of the questions we’re investigating.

And yet, after two short days, the Edwards Lab, with help from the Konar Lab, pulled the chambers out of the water and we began to prepare for our steam to our next and final island: Yunaska. I’d like to give a special shout-out to the Oceanus’s 2nd mate, Jeremy Fox, for putting up with my dad jokes as he diligently changed my bandages once a day. Stay tuned, we’ve only got one more island to go! Cheers, -Baron von Urchin  The Wecoma buzzes the bow of the Oceanus on our way to one of our dive sites The Wecoma buzzes the bow of the Oceanus on our way to one of our dive sites Kiska Island 7/17/2017 Anybody who’s worked on the water will tell you to always be on your toes, ready for anything the ocean, can throw at you. After leaving the Semichis we headed ever eastward to our next sampling station. After a day-long steam, and some much needed R&R we arrived on Kiska and immediately got to work. Like Attu, Kiska saw its fair share of action during the Second World War. Our serene anchorage in Kiska Harbor afforded us amazing views of the island, whose pock-marked hills bear the scars of battle. The site selection and chamber set up on day one went without a hitch; by now this routine was second nature to us. During our first day a handful of us were even allowed to go ashore and check out some of the remnants from the bitter conflict all those years ago. We’re all eager to explore the reefs that ring these incredible islands, but walking through the tall tussock grass clinging to the rocky landscape provides a fresh perspective and invigorates us to no end. The air may be cold, and the water colder, but we all know just how luck we are to work here.  Tristin drives the Wecoma as we prepare to beach-land on Kiska Tristin drives the Wecoma as we prepare to beach-land on Kiska However, on the morning before our chamber recovery dive, life threw me a curveball. Working in, on and around the water has inherent risks which we do are best to be cognoscente of. But sometimes you pull a fast one on yourself without any help from outside sources. Just before I planned to get suited up for our dives, I managed to get a finger caught in a door and had to get pulled from the dive. Without much time to spare, the team went on without me, leaving me in the more than capable hands of the Oceanus’s second mate and medical officer. After a successful chamber recovery, we stowed and stashed our gear and conducted the typical trawl surveys. After that we headed back to Adak, which took another 10 hours or so. We stopped on Adak just long enough for Scotty to pick up an experiment he had left running for the last two weeks, and for me to visit the medical clinic. Don’t get too excited, this is just a precaution; the risk of infection is high out here and no one wants to take any risks.  The author receives medical attention from a community healthcare provider at the clinic on Adak The author receives medical attention from a community healthcare provider at the clinic on Adak And, actually, visiting the clinic on Adak was a really great experience. To say that Adak is a ghost town is an over statement; only a handful of people live in a town of mostly abandoned buildings. The medical center opened early, just for me. My lab mate, Tristin, escorted me to the clinic, which is housed inside the all-in-one high school, post office and town hall. We were cheerfully greeted by two administrators, two nurses and a community health associate. This skeleton crew of healthcare professionals are responsible for providing take care of the few isolated communities scattered between Dutch Harbor and Attu. I knew I was in the best of hands when they immediately started joking and heckling me; these rough ladies laughed and joked with me while getting me “fixed up”. As it turns out, I managed to fracture as small part of my finger and give myself some pretty sever lacerations; I won’t be able to dive for the rest of the trip. Now we're heading east to our next island; Atka. If this island rings a bell, it’s because we sampled Atka last year during our first cruise. However, last year we ran into some rough weather and, as luck would have it, we were given the opportunity to resample without jeopardizing this year’s cruise.

Stay tuned, as we head back to Atka for another round! Cheers, -Baron von Urchin  Once we arrive at a new island, the Edwards Lab assembles the sensor stands that are vital to this project Once we arrive at a new island, the Edwards Lab assembles the sensor stands that are vital to this project Nizki Island 7/14/2017 Another day, another deployment. We’ve been in the Aleutians aboard the r/v Oceanus for just over a week now, diving in frigid water almost every day now. After trawling on Attu, we began our steam eastward; in the pre-dawn gloom we “dropped hook” in a small island cluster known as the Semichis. As we stumbled out of our bunks and towards the galley, following the smell of breakfast and hot coffee, a peculiar sight caught my attention; lights in the distance. Deceived by a brain still half-asleep, it took me a minute to process what I saw. Since leaving Adak the last week the only sign of humans we’ve seen have been remnants of WWII and the flotsam that’s washed up on the beaches. Here, in one of the most remote places on the planet, we hardly expect to see another living soul. And yet, what looked like a small city twinkled persistently on the horizon. As the sky began to lighten I realized what we were seeing; the military base on Shemya. During the Cold War the US built a top-secret radar station here, and to this day the ominous “boom box” still listens for ballistic missiles, should they enter US airspace. But we’re not here in the Semichis to gawk; we have our experiments to deploy and samples to collect. As stated before, the benthic productivity chambers (three in each of three habitat-types) are a beast to deploy. It takes all five divers from the Edwards Lab to set them up; we use lengths of heavy chain and whatever rocks we can find to make sure our chambers, and their respective sensors, stay upright all through the day and night.  Dr. Edwards looks into the fog as the author drives the inflatable "Wecoma" to our dive site Dr. Edwards looks into the fog as the author drives the inflatable "Wecoma" to our dive site For those of you that might have missed it, inside each chamber we mount an oxygen and temperature sensor and a PAR sensor. PAR stands for “photosynthetically active radiation” or, more simply, the specific chunk of the light spectrum that plants and algae use for photosynthesis. The productivity chambers allow us to gain an understanding of what’s going in a fixed volume of water, which is important when we go to calculate the overall productivity of a system. What do we mean by productivity? We’re essentially looking at the difference between production (measured in the amount of oxygen produced) and respiration (the amount of oxygen consumed). Plants (and algae of course) and animals respire, but only photosynthesizers produce oxygen. Once we have a measurement of oxygen produced/consumed inside the chambers, we can compare that to the data gathered by the sensors we leave outside of the chambers, which are recording what’s going on in the environment. At the end of the 24-hr deployment, we “ground-truth” our measurements by collecting all of the organisms inside of the chambers when we go to pick them up and measure their biomass onboard the Oceanus. All the while we’re at sea, diving and steaming between islands, a colleague from a university in Korea, Dr. Ju-Hyoung, and another Edwards Lab member, Sadie Small, run onboard experiments so we can get measurements of individual species’ rates of oxygen consumption/production.

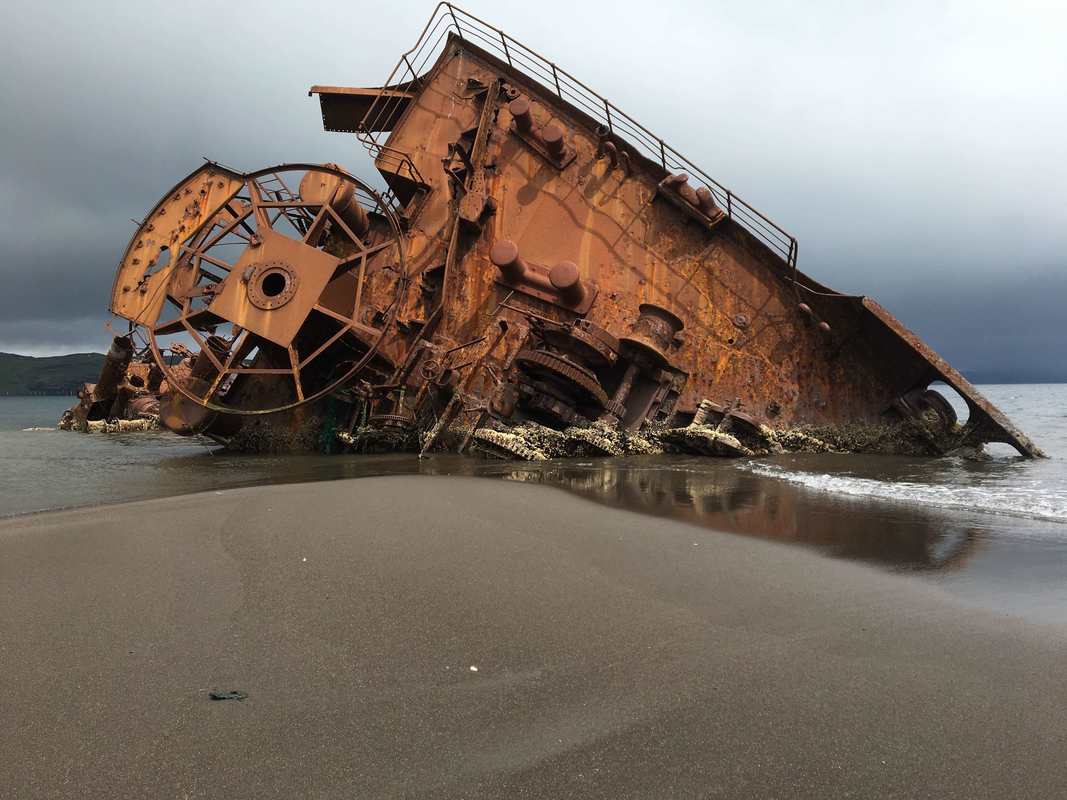

Alright, I think that’s enough ecology for today. Be sure to check back in, after the Semichis we’re heading east again towards yet another island. Until then, this is Baron von Urchin checking in from the Aleutian Archipelago  Attu Island 7/12/2017 “This isn’t the end of the world, but you can see it from here” is supposedly written on a sign at the lonely US Coast Guard outpost on Attu. This island of extremes is the furthest west chunk of land you can go in North America; apparently we crossed the international dateline shortly after we steamed west from Amchitka. Attu saw pretty severe fighting between the US and entrenched Japanese soldiers during the second World War, but you’d never know it by the vistas afforded to us from our anchorage in Holtz. Most of us, at least from San Diego, were secretly eagerly awaiting our deployment to Attu. What would it be like all the way west? Would the wind be constantly howling across the Near Straight? Would the water be unbearably cold? What would the rocky reef communities look like? Our benthic experiments did their job without causing us any grief, affording us time to work on other projects. By the end of this year’s cruise our labs will have enough data to tell some very interesting stories, so be sure to stay tuned for that. In the meantime, we enjoyed the sites Attu had to offer with breathless amazement. We were even afforded shore-leave. Exploring the island on foot for a brief few hours did little to satisfy our curiosity. But, all too soon we had to pack up our experiments, stow the small boats on the Oceanus’s deck and begin our steam back east. For the rest of the trip we’ll be stopping at several more islands as we make our way eastward to Dutch Harbor on Unalaska, and our departure from the Aleutians.

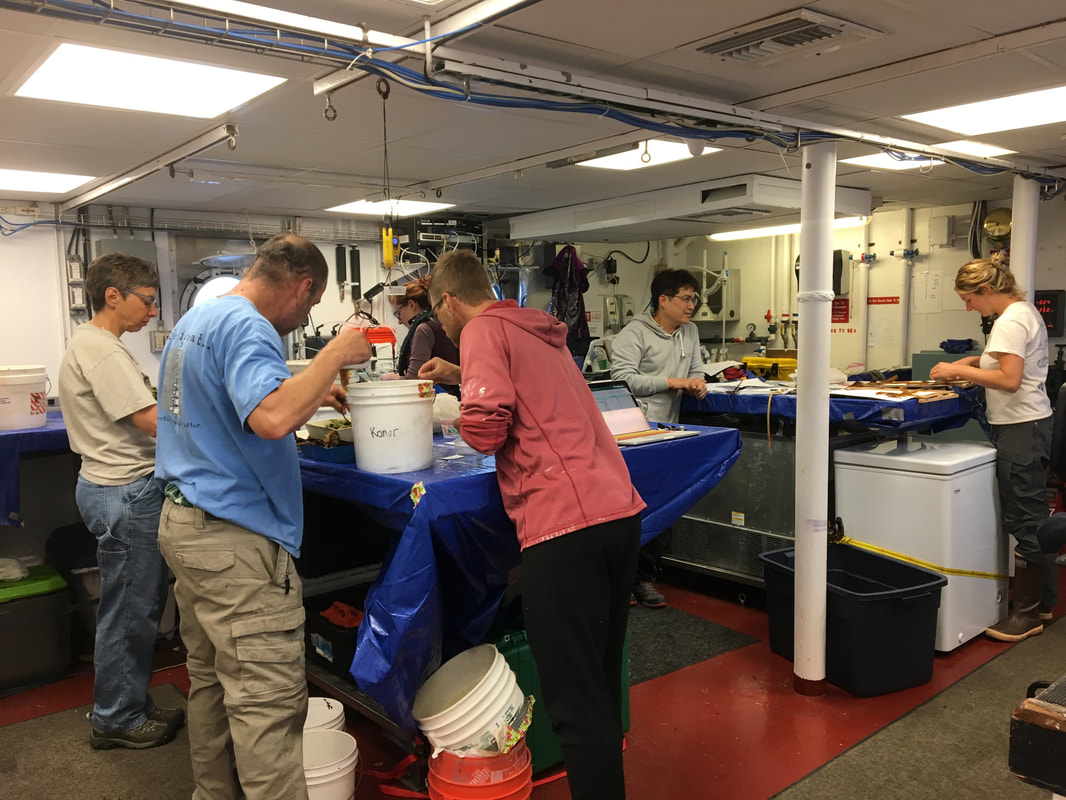

Stay tuned, we’re making our run to the Semichi Islands; Shemya, Nitsky and Allied. Until next time, -Baron von Urchin  A rare site; Mt. Moffett emerges through the clouds above Adak A rare site; Mt. Moffett emerges through the clouds above Adak Amchitka Island, Aleutians July 10, 2017 It’s a strange sensation, waking up in the pre-dawn heat of what promises to be a sweltering summer day in Southern California, only to find yourself stumbling out of a small plane in blustery Arctic winds that very same evening. The first thing that greets you as you step out onto the tarmac on Adak Island is the dry, salty air whipping past you and a sign above the terminal building that reads, “Welcome to NAF Adak, Alaska, Birthplace of the Winds.” Well, here we go again. For those of you who might have missed it, last year we sampled six islands in the eastern Aleutians; this year we’re targeting at least five more in the west, all the way west. The “science party”, that is, the Edwards Lab and the Konar Lab, convened in Anchorage before our flight to Adak. Along the way we traded stories, most of us hadn’t met in person since last year’s cruise. Once on Adak we got right to work loading our gear onto the r/v Oceanus, our home for the next three weeks. After we set up our wet and dry labs, stowed away dive gear, and got settled in to our cabins, we had a safety briefing and got ready for our cruise. In the morning we began our “steam” (transit) to Amchitka Island, our first stop. It was uncanny how quickly we settled right back in to our old routine. Life aboard a research vessel is singular, and unlike any experience on land. We picked up right were we left off last year, as if we hadn’t missed a beat. The Konar Lab got down to business as they always do, tirelessly diving and collecting samples. Meanwhile we in the Edwards Lab prepared to deploy our experimental chambers along the rocky shores of Amchitka Island. Using historic data, both labs are targeting kelp forests, urchin barren grounds and the “transition” state between the two. Collectively, we hope to gain a better understanding of patterns of biodiversity and productivity along these beautiful yet elusive islands. Our dives went well, even though as a group we were just a little bit rusty when setting up our first of nine tents. But at the end of our first day we were right back into the swing of things. On July 9th, we pulled up our experiments and prepared everything for our next island. As with last year, after we finishing sampling an island (which takes about two full days) we conduct three trawls from the back deck of the Oceanus. All in all, it took all of us nearly the entire night to finish sorting the SCUBA and trawl samples. Exhausted but happy, most of us didn't "rack out" until after 3am. Fortunately, we have another steam ahead of us which means we sort of get a day off, at least from field work. It takes nearly 24 hours to steam from Amchitka to our next island, the furthest west in the Aleutian Archipelago: Attu. By the time we get there we'll be recharged and ready to jump back in the water. Stay tuned, we’ve only just begun to sample! Cheers, Baron von Urchin

July 5th, 2017

Los Angeles, CA Hey everyone, it's that time of year again; on Thursday July 6th the Edwards Lab will be joining the Konar Lab (University of Alaska Fairbanks) for our second and final Aleutians cruise! For the next three weeks we'll be sailing aboard the r/v Oceanus, living and working in the cold nearshore ecosystems of the Bering Sea. Our mission is to dive on these remote rocky reefs, and to quantify the changes these systems are experiencing. We'll be coupling subtidal surveys with experiments to see how the loss of kelp and kelp forests affects patterns of diversity and productivity.

Be sure to follow along here, and on our project-specific site. For more information, check out this fun video from last year's cruise, and this one that was made up for a museum exhibit in Dutch Harbor, Alaska.

That's all for now folks! See you in the great white north!

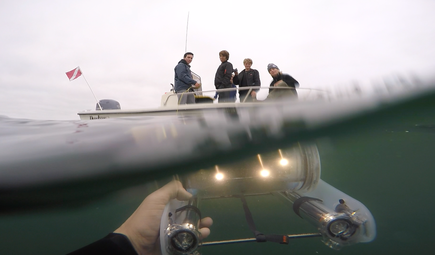

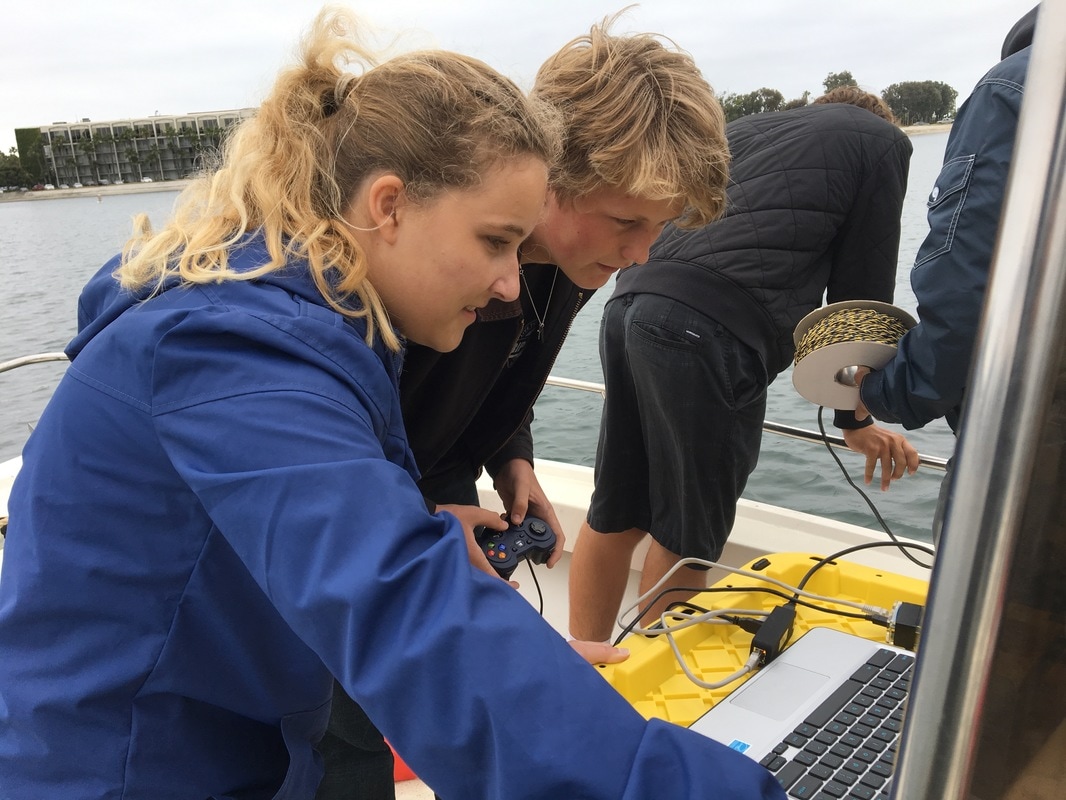

Cheers, Baron von Urchin  Mission success! Pegasus "poses" in front of the topside crew Mission success! Pegasus "poses" in front of the topside crew 6/7/2017 San Diego, California Nearly three months of planning, preparation, and hard work have gone into this fateful day: Pegasus’s first plunge in salt water. From day one, when we opened our kit and started assembling our little ROV, the team has talked of almost nothing else. All of our hopes and aspirations rested on a successful first flight in salt water. In order to make sure everything went smoothly, we decided to test Pegasus in the shallow and protected waters of Mission Bay. On a cold and overcast Wednesday afternoon Project Pegasus team members set off on one of SDSU’s small boats, with the help of boat-handler extraordinaire (and fellow grad student/Edwards Lab mate) Tristin McHugh. We anchored in a shallow cove and prepared Pegasus for a fateful first dive. As it turns out, we experienced quite an emotional rollercoaster. All systems were a go; however, as we moved to drop our ROV in the water the camera image seized (much like our previous issue with the lasers). After rebooting the system, we tried again; and just like the first time just as we were about to drop Pegasus in the water the camera froze again. This happened not once, not twice but fives times! After our sixth reboot we decided to go for it… resulting in a flawless 35min dive! Our first “flight” of Pegasus took us on a tour of the murky water, through seagrass beds and around the boat. We quickly learned the nuances of a successful flight. As it turns out, Pegasus is a little heavy! Our negatively-buoyant ROV requires a lot of thrust to propel it through the water. We even learned what to do in the event of “entanglement” in environmental hazards, such as seagrass! After three months I’m delighted to say Project Pegasus is a success. I’m incredibly proud of all of the hard work, dedication, and cohesion displayed by Project Pegasus team members. We all learned a suite of skills along the way, adding new tools to our toolboxes. However, it’s now time to pack up Pegasus in preparation for the Edwards Lab’s second research expedition to the Aleutian Islands.

Stay tuned! There will be plenty of updates from the Aleutians. And when we get back in the Fall, Project Pegasus will meet again to discuss a whole host of new projects for Pegasus. Thanks for following us along this incredible journey! Cheers, Baron von Urchin  Lights, camera, action! Lights, camera, action! 6/4/17 San Diego, CA Sunday, June 4th was a momentous day for Project Pegasus; a lot of time, energy and prep-work went in to our first in-water test. However, before we could submerge our little robot, we first had to do a final bit of soldering. After the team and I installed external light cubes, which will allow Pegasus to shed extra light in the deep dark water, we did one final pre-dive safety check. Here’s what Project Pegasus intern Maddie had to say: “Today is the day we’ve all been waiting for…putting Pegasus into the test pool! Our team has worked extremely hard to get to this point and we wouldn’t have been able to accomplish this feat alone. With everyone’s participation and unique skills, the box of various ROV components was soon transformed into a masterpiece that we call Pegasus. Despite the small problems we ran into during the build, Pegasus is definitely a top notch ROV. But we had one more thing to put on before Pegasus was in the water- the light cubes! This entailed hot gluing the two tiny (yet very bright) cubes onto the sides of the structural unit and soldering the wires to the control panel. Afterwards, we moved on to testing out the game controller that we will be using to control the lights, propellers, direction, and camera angle on Pegasus. It was truly amazing to see Pegasus come alive, something our team will never forget. Then came the most exciting moment; water time! We carried the computer, controller, and Pegasus out to the test pool and set everything up, making sure that this exciting event would run smoothly. We were all very nervous because we didn’t want our hard work to result in a flooded or destroyed of Pegasus. Team member, Lorenzo, got the honors of putting Pegasus into the water. Unfortunately, we had to pull it out within a minute because the camera wasn’t working, but we restarted it and put it back in the water. The camera then worked normally; the propellers allowed Pegasus to move, and the team was stoked! We each got a chance at using the game controller and viewing the action through the camera that sends live footage back to the computer. It was very exciting to see our ROV operating underwater! Aside from a few hiccups, everything went well and our team was thrilled!” What a day indeed! It’s hard to believe that we’ve just wrapped up the construction phase of Project Pegasus. It has been an incredible process; I’m honored to have worked with such a dedicated and committed group of scientists-in-the-making. However, as Maddie said, we’re not out of the woods yet. We’ve got just a little bit more troubleshooting before we can pack up little Pegasus and send it off to the Aleutians!

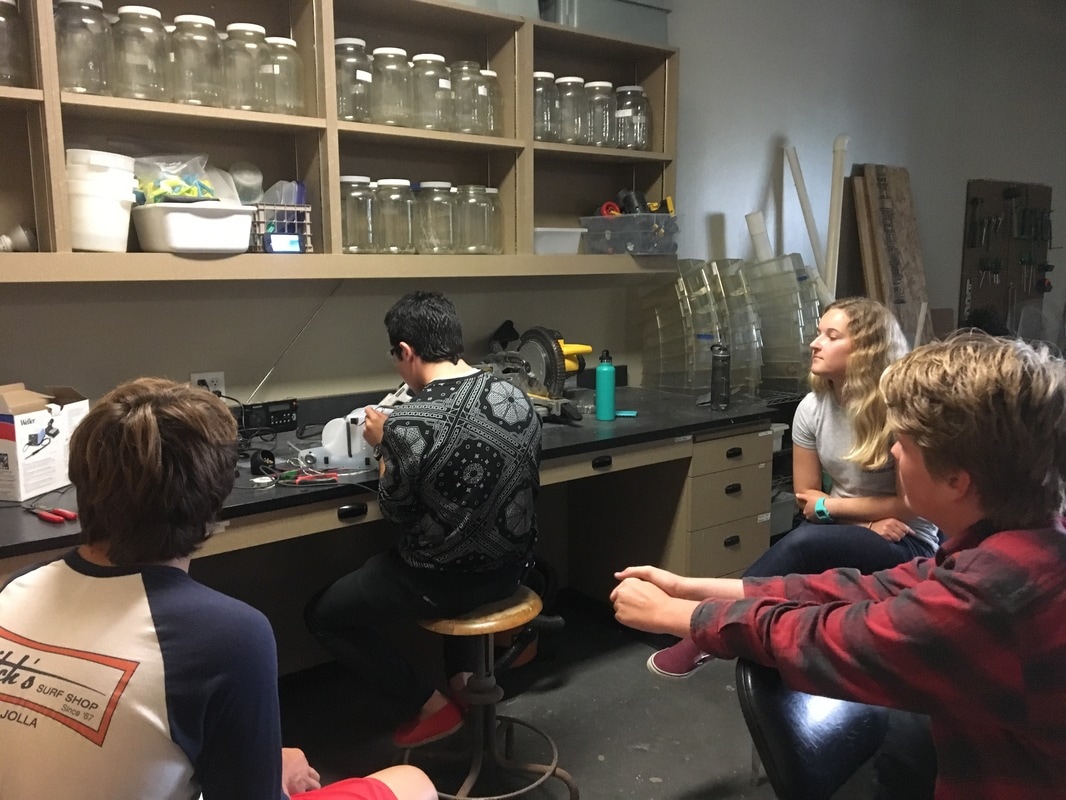

Stay tuned, next time Pegasus will get its first taste of saltwater! Cheers, Baron von Urchin  Project Pegasus team members see themselves through the "eye" of Pegasus for the first time Project Pegasus team members see themselves through the "eye" of Pegasus for the first time 5/24/2017 - 6/1/2017 San Diego California We’ve officially reached the end of the modules for the construction of little Pegasus, and the team and I couldn’t be more thrilled! We’ve broken this post into two days because we ran into a little bit of an issue the first time we tried to turn on Pegasus. After charging the high-capacity lithium batteries that give our little ROV the juice it needs to run, we couldn’t get any feedback from the ROV itself. After a whole lot of head scratching, and a lot of time digging through internet forums, we realized that our batteries weren’t making contact in the battery tubes. After this “ah-ha’ moment all we had to do was solder a little bit of material onto the positive end of each battery so that they make good contact in their tubes. And then, violà! Little Pegasus came to life! But, our trouble shooting issues didn’t stop there.  Team member Jordan solders the tether connection while Maddy steadies Pegasus Team member Jordan solders the tether connection while Maddy steadies Pegasus Here’s what Project Pegasus intern Jordan had to say about these last two days: “5/24/17 The ROV is very close to completion. We were able to turn the ROV on and we saw the light show that it produced. It was a very cool sight to see, the ROV flashing its lights, especially because I know that we did all of the wiring and soldering in order to make it happen. We did some troubleshooting today with communication back from the ROV. The ROV would turn on but it wouldn’t send us communication back, which was problematic. For the sake of time we decided to move on and email OpenROV™’s [tech support] people about the issue. Next, we placed the O-rings on the battery tubes and the DB25 pin connector to make sure they are water tight. At this point in the construction of the ROV, there were no more directions. Because of this, communication with the team was crucial in order to make any new adaptations to the ROV. We wanted to solder a waterproof quick release to the ROV so that we would be able to disconnect the 100m long tether from the ROV. We were not sure how close to the ROV we wanted to solder the quick release, but we decided together what length we would solder it at.  Team member Maddy puts the finishing touches on a joint Team member Maddy puts the finishing touches on a joint 6/1/17 We had the amazing opportunity to video chat with Ms. Samantha [Wishnak] from the e/v Nautilus about their massive ROV called Hercules. She was able to talk to us about her daily life on the research vessel and how her team uses Hercules to obtain scientific data. Talking to her and asking her questions was very enlightening because many of us on our team want to pursue a career in ocean science and possible do exactly what Samantha is doing right now. After the video chat we got to work on finishing the ROV. The first thing we did was try to align and set the lasers on the ROV. There are two red lasers on the front of the ROV right next to the camera. These lasers measure how far away certain objects are from the ROV. This information will be important, along with live visual data from the ROV, to determine how close we want to get to an object underwater. We weren’t able to calibrate the lasers to what the directions wanted. The lasers were actually crossing, so the left laser was creating the right dot 3 meters away, and the right laser was creating the left dot 3 meters away. This is very problematic because that means the lasers are traveling at an angle, so the laser is going to travel further to hit the same object, which will make our measurements inaccurate. The last thing we did today was a very long and tedious task. We have 100 meters of [tether] cable that came with the ROV, but we want to line all of it in black [expandable PET] webbing to protect the tether. Essentially we needed to feed the 100-meter tether though the black webbing. On top of that the 100-meter cable was very mixed up in the ultimate tangled headphone conundrum. We split off into two teams; one team’s job was to try and untangle the mess of cable, and the other team’s jobs was to feed the cable through the black webbing. We switched off jobs here and there but it ended up taking us nearly two hours. By the end of two hours we had untangled the the monster and made great progress feeding the tether through the black mesh. It was a very rewarding moment in the end. Even though this process wasn’t very exciting, like soldering or solvent welding, it was a necessary step to reach our ultimate goal of completing the ROV.” Great job team! I’m incredibly proud of all of the team members; their dedication and commitment has really paid off.

Stay tuned, the next time Project Pegasus meets we’ll be submerging Pegasus in water for the first time!!! The clock is ticking; the Edwards Lab leaves for Alaska in just over one month! Cheers, -Baron von Urchin |

AuthorPike Spector is currently a Research Operations Specialist with Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary Archives

August 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed